Is Hiv A Rare Disease – AIDS-related illnesses have claimed more than 32 million lives since the beginning of the HIV epidemic in 1981. The death toll, social impact, and economic effects of the HIV epidemic have made HIV/AIDS one of the greatest threats to public health made that the world has ever known. Governments, companies and individuals have collectively spent trillions of dollars on the development of effective treatments and the search for an effective vaccine or cure. Today, antiretroviral drugs (ART) make HIV a manageable condition, but neither a vaccine nor a cure is available. However, the fight for a cure is not over, and new biotechnologies may finally provide a definitive cure for people living with HIV.

Without medical intervention, HIV infection is inevitably fatal. ARTs have slowed the rate of new infections and reduced the number of deaths since the peak in 2004. However, these drugs significantly affect quality of life, and the stigma of infection remains. Worldwide, there are approximately 38 million people living with HIV who would benefit from a cure, so why isn’t there a cure yet? In short, curing HIV is very difficult. To explain why, we’ll list the top five challenges in HIV cure research, then we’ll talk about how new gene therapy techniques could finally push HIV cure research over the finish line.

Is Hiv A Rare Disease

Retroviruses, class VI in the photo below, are unique because of their ability to exist in RNA form, then transition to a DNA form to become a permanent part of the cell they infect. The cell can then reread the DNA “master copy” of HIV and make new RNA versions of HIV to export to other cells. During the transition from RNA to DNA and DNA to RNA, errors can occur, giving retroviruses such as HIV the high mutation rate of an RNA virus with the permanence of a DNA virus.

What Are The Rare Diseases That Cause Peripheral Neuropathy?

Figure 1: The Baltimore system, as illustrated by Dr. Racaniello, host of This Week in Virology, a staff favorite at Addimmune

In the 2017 paper, Recent Advances in Understanding HIV Evolution, Andrews and Rowland-Jones comment on HIV’s mutational potential: “HIV evolves extremely rapidly, showing the highest recorded biological mutation rate currently known to science.” The mutation rate allows for the rapid generation of a wide variety of HIV variants, which the authors identify as “a major contributing factor in the failure of the immune system to eradicate the virus.”

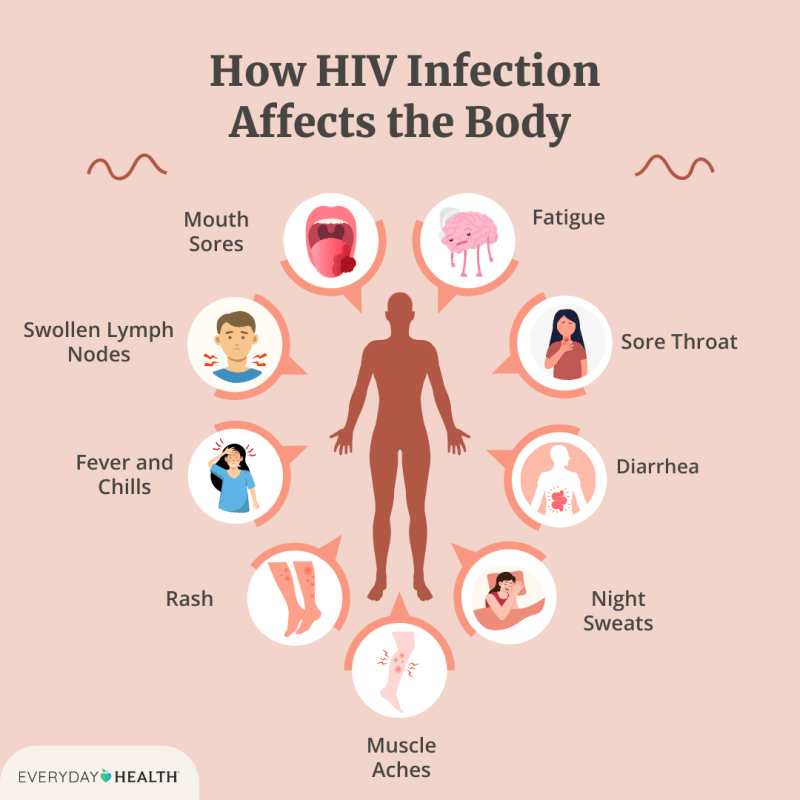

Another major obstacle to curing HIV is that the virus infects and negatively affects immune cells, the cells needed to fight an infection. HIV primarily infects the subset of immune cells called CD4+ “helper” T cells, which play a central role in the immune system. So, when HIV kills helper T cells, it causes immune deficiency. T cells are mobile, heterogeneous, and capable of rapid cell division, making them ideal hiding places for HIV. Additionally, because HIV can hide in the DNA of a helper T cell, when the cell divides, its daughter cells carry the HIV genome, creating new HIV-infected cells without the need for cell-to-cell spread of HIV.

The T-cells of the immune system divide in response to pathogens, so ironically, T-cells meant to fight HIV produce more HIV-infected cells and become a major source of the virus in the body. Once HIV destroys the T cells responsible for the anti-HIV response, it can replicate uncontrollably and destroy the rest of the helper T cells, opening AIDS and the body to opportunistic infections and certain forms of cancer.

Women And Hiv In The United States

Viral latency is another major obstacle to an HIV cure. In a nutshell, latency is when a virus infects a cell, but does not immediately start making new viral copies. Latent, resting HIV-infected cells can remain in reservoirs in the body for months or even years and become active at any time. Since current antiretroviral treatments (ARTs) target HIV itself, these drugs are unable to eliminate latently infected cells because they do not actively produce viral particles. For the same reason, latently infected cells cannot be identified and eliminated by the immune system. Thus, eliminating the reservoir is the biggest challenge for the scientific community.

In a recent ScienceDaily article, the latent reservoirs were considered “the main obstacle to curing HIV/AIDS.” The article describes work done by a team of Gladstone visiting scientists, led by Nadia Roan, in which a set of cells were identified that “preferably support latent infection by HIV.” The cells have a surface protein, CD127, and are “found in tissues such as lymph nodes…” Roan concluded, “our findings suggest that CD127 cells from tissues may be an important population to target for an HIV cure.” If further research is carried out to identify all the sneaky places where HIV hides, one thing is certain, a full functional cure for HIV would be needed to tackle the infected cells of the viral reservoirs, if they show themselves.

While ARTs are not a cure, this cocktail of drugs stops the progression of HIV to AIDS by targeting HIV at different stages of its replication cycle. Modern ARTs make it possible for those with HIV to live a near-normal lifespan with the caveat of having to take medication regularly, while living with uncertainty about HIV resurgence – turning HIV from a death sentence to a life sentence. Since ARTs can be used to halt disease progression and minimize transmission, the continued use of ARTs, rather than the search for a cure, forms the basis of most approaches to eradicating HIV.

The UNAIDS 90-90-90 goal for the “post 2015 era” approaches the HIV epidemic from a public health perspective and aims to eradicate HIV by 2030. By minimizing new infections, it is possible to to eradicate disease without the existence of a cure. In fact, that’s how we got rid of smallpox. UNAIDS sets out a series of goals that call on people to first become aware of their HIV status, then to start treatment, and then to suppress the virus through the use of ARTs and behavior informed by their HIV status. Although this approach does not provide help to those already living with HIV, it is expected to control the spread of HIV, making it increasingly less likely that new infections will occur.

Diagnostic Model Of Talaromycosis In Hiv/aids Patients

However, a shortcoming of the movement to eradicate rather than cure is that in times of upheaval, such as that caused by COVID-19, efforts to work towards eradication are in danger of being sidelined. In May 2020, the UN issued a “wake-up call” to remind global leaders of the continued need for treatment in areas of the world where the greatest loss of life is most likely to occur if the spread of the disease is not is avoided. Eradication is a positive goal for the preservation of life for future generations; but again, it is not a cure for the 38 million people currently living with HIV.

It seems simple enough to agree on what an HIV cure is, yet there are two different types of cures envisioned. Theoretically, if it were possible to eliminate all traces of HIV from the body, such an approach would be called a sterilizing cure. The other type of cure is a functional cure, where the levels of HIV in the body are kept below the level of detection without the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART). In the case of a functional cure, the infected person would not need antiretroviral medication, would not experience the effects of HIV, and would not transmit the virus to anyone else. This is a cure because there would be no need for ART – ever – unlike a remission, where the disease returns.

Researchers have been searching for both types of cures for decades, and Addimmune’s ongoing human trials for a functional cure show the progress that has been made over the years. Our approach builds on the lessons learned from case studies such as those of the Berlin patient and the London patient, who were declared cured of HIV, as well as previous genetic approaches to HIV, such as Sangamo’s SB-728-T.

A cure for HIV/AIDS has eluded researchers for decades. The interactions of the virus with the immune system make it difficult to cure, because HIV can command the T cells that are responsible for defeating it. This reduces the number of T cells that mount an effective anti-HIV response and turns them into HIV reservoirs. HIV also mutates at one of the fastest rates known to science, so it is so far impossible to treat with a single drug. The virus can also hide for longer periods, latently, in infected cells to avoid detection.

Cardiovascular Disease Among Persons Living With Hiv: New Insights Into Pathogenesis And Clinical Manifestations In A Global Context

The lack of agreement on how to approach the HIV epidemic splits resources between cure research and public health approaches. The potential diversion of funds to eradicating a cure is likely to leave lifelong use of ARTs as the only means for people living with HIV. While reducing the number of HIV infections has a positive impact on public health, for those living with

Hiv is a curable disease, is hemophilia a rare disease, what is a rare disease, is als a rare disease, is ms a rare disease, is hiv a disease, hiv is a communicable disease, hiv is a chronic disease, is hiv a blood disease, is lupus a rare disease, is hiv rare, how rare is hiv